In the 1930s many programs were created that helped people financially and also provided support for communities.

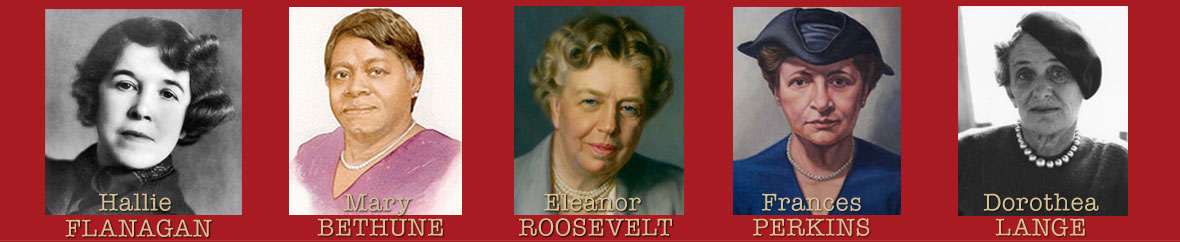

Frances Perkins, the first woman on the U.S. Cabinet as Secretary of Labor under FDR. The unsung hero behind the creation of Social Security, the Works Progress Administration, a federal minimum wage and workplace safety standards, Perkins was also a fierce defender of immigrants and a trailblazer for women’s independence.

The Social Security Act of 1935:

- It was an insurance plan. Prudent policy required collecting revenue during good times instead of scrambling amid downturns when state coffers were empty.

- It was a federal plan. Every congressional delegation knew that if states had to set up their own systems, they’d end up racing each other to the bottom

- It was a big plan, which recognized that everything and everyone was connected. It recognized that unemployed people paid no taxes and didn’t shop in local stores; that sickness or injury left families homeless and children badly educated; that elderly poor people were a drain on the resources of families and the states. They knew that a bad economy hurt everyone, not just the unemployed.

Currently, 94% of wage earners in America pay into Social Security on all of their earnings, but the top 6% do not.

The Social Security Act also created unemployment insurance, funded by companies, to discourage seasonal layoffs and weekly hiring and firing. That became a source of economic stability, leveling out booms and busts. Direct government funding for the unemployed, including food stamps and hiring for infrastructure construction, increases economic activity by more than a dollar and a half for each dollar spent.

In hard times, this government-subsidized spending allows many stores to keep their doors open. In contrast, today’s tax cuts for the wealthy cost a dollar for a boost worth only 30 or 40 cents to the economy.

United States Housing Act (1937)

President Roosevelt signed the United States Housing Act into law on September 1, 1937. The purpose of the law was, “To provide financial assistance to state and local governments for the elimination of unsafe and unsanitary housing conditions, for the eradication of slums, for the provision of decent, safe, and sanitary dwellings for families of low income, and for the reduction of unemployment and the stimulation of business activity, to create a United States Housing Authority, and for other purposes.”

Between September 1937 and June 1941, the USHA lent about $800 million towards the construction of 587 low-rent housing developments, as well as some housing for defense industry workers, creating over 170,000 dwelling units. Tenants were typically expected to pay half the rent, with federal, state, and local governments pitching in the rest.

A driving force behind New Deal housing policies was Catherine Bauer Wurster who wrote the classic volume ‘Modern Housing’ and served as Director of Research and Information for the USHA.

Section 1 of the U.S. Housing Act of 1937 states: “It is hereby declared to be the policy of the United States to promote the general welfare of the Nation…” Here, we see another example of how New Deal policymakers embraced the “general welfare” sections of the U.S. Constitution (i.e., the Preamble and Article I, Section 8), as opposed to narrowly focusing on the “common defense” sections.

But public housing has always been highly controversial in the United States, where private supply prevails. While public provision would continue after the war, it would be overshadowed by urban renewal programs launched by the housing acts of 1949 and 1954.

In the 1960s, there would be a brief revival of public housing under President Johnson’s Great Society and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development was created. Federal support for public housing continues today in modest ways, such as the Section 8 housing assistance program which is woefully underfunded and waiting times are long, measured in years.